This image shows the LHCb detector along with a large number of collaboration members on the floor of the detector hall. LHCb, rather than being a complete detector around the collision point, only measures particles whose moment carries them in one particular direction: a directional detector. This design enables the best-ever study of b-quark containing baryons and mesons, leading to the discovery of baryonic CP-violation, for the first time, in 2025.

Credit: CERN/Maximilien Brice, Rachel Barbier

Key Takeaways

This image shows the LHCb detector along with a large number of collaboration members on the floor of the detector hall. LHCb, rather than being a complete detector around the collision point, only measures particles whose moment carries them in one particular direction: a directional detector. This design enables the best-ever study of b-quark containing baryons and mesons, leading to the discovery of baryonic CP-violation, for the first time, in 2025.

Credit: CERN/Maximilien Brice, Rachel Barbier

Key Takeaways

- One of the biggest unanswered questions in all of theoretical physics is how the Universe came to have more matter than antimatter in it.

- In laboratory experiments, we can only create or destroy matter if we also create or destroy an equivalent amount of antimatter. But at some point in the Universe’s past, it must have happened.

- Although it flew under most people’s radar, a set of 2025 discoveries from the LHCb collaboration brought us a step closer to the solution than ever before.

The immensity of the Universe fills us with wonder.

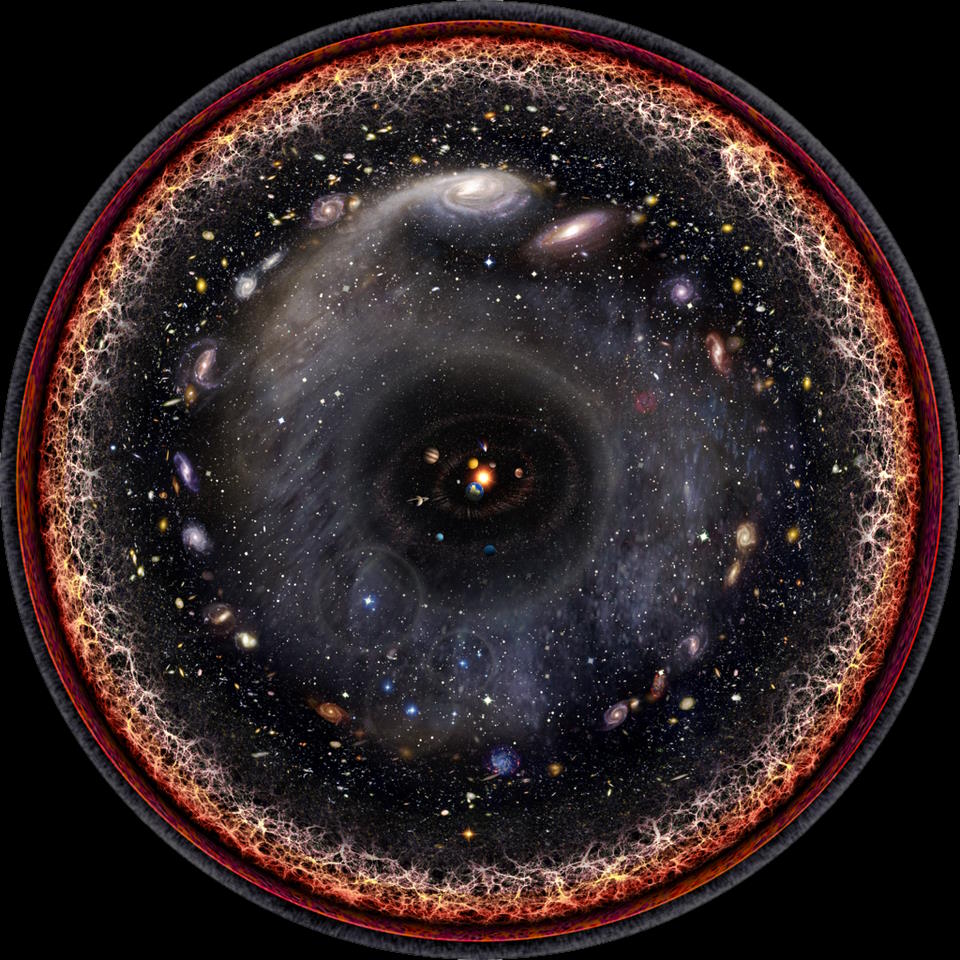

Artist’s logarithmic scale conception of the observable universe. The Solar System gives way to the Milky Way, which gives way to nearby galaxies which then give way to the large-scale structure and the hot, dense plasma of the Big Bang at the outskirts. Each line-of-sight that we can observe contains all of these epochs, but the quest for the most distant observed object will not be complete until we’ve mapped out the entire Universe.

Credit: Pablo Carlos Budassi; Unmismoobjetivo/Wikimedia Commons

Artist’s logarithmic scale conception of the observable universe. The Solar System gives way to the Milky Way, which gives way to nearby galaxies which then give way to the large-scale structure and the hot, dense plasma of the Big Bang at the outskirts. Each line-of-sight that we can observe contains all of these epochs, but the quest for the most distant observed object will not be complete until we’ve mapped out the entire Universe.

Credit: Pablo Carlos Budassi; Unmismoobjetivo/Wikimedia Commons

Despite all we’ve learned, however, unsolved puzzles abound.

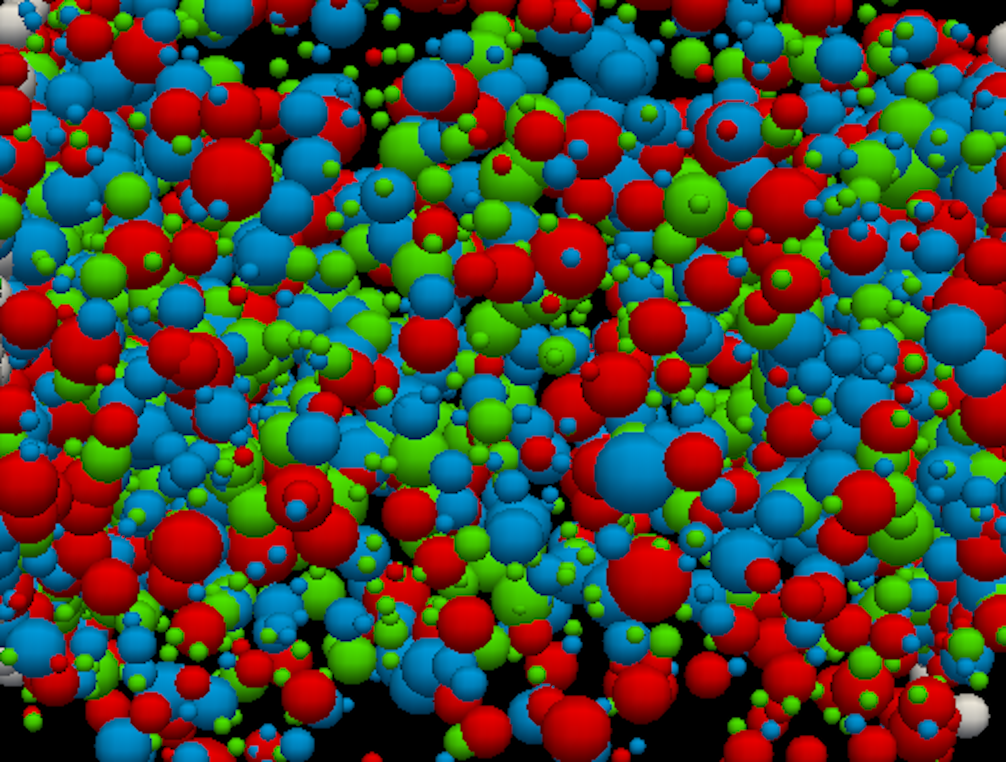

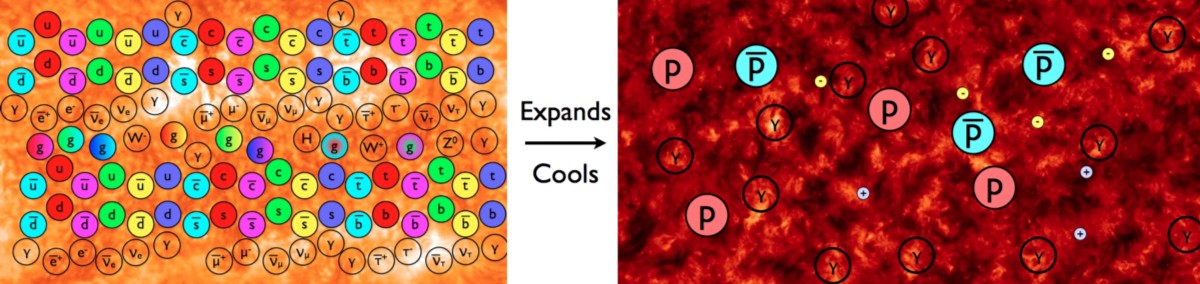

The early Universe was full of matter and radiation, and was so hot and dense that it prevented all composite particles, like protons and neutrons from stably forming for the first fraction-of-a-second. There was only a quark-gluon plasma, as well as other particles (such as charged leptons, neutrinos, and other bosons) zipping around at nearly the speed of light. This primordial soup consisted of particles, antiparticles, and radiation: a highly symmetric state.

Credit: Models and Data Analysis Initiative/Duke University

The early Universe was full of matter and radiation, and was so hot and dense that it prevented all composite particles, like protons and neutrons from stably forming for the first fraction-of-a-second. There was only a quark-gluon plasma, as well as other particles (such as charged leptons, neutrinos, and other bosons) zipping around at nearly the speed of light. This primordial soup consisted of particles, antiparticles, and radiation: a highly symmetric state.

Credit: Models and Data Analysis Initiative/Duke University

All the planets, stars, and galaxies we see are composed of matter, not antimatter.

Through the examination of colliding galaxy clusters, we can constrain the presence of antimatter from the emissions at the interfaces between them. In all cases, there is less than 1-part-in-100,000 antimatter in these galaxies, consistent with its creation from supermassive black holes and other high-energy sources. There is no evidence for cosmically abundant antimatter.

Credit: G. Steigman, JCAP, 2008

Through the examination of colliding galaxy clusters, we can constrain the presence of antimatter from the emissions at the interfaces between them. In all cases, there is less than 1-part-in-100,000 antimatter in these galaxies, consistent with its creation from supermassive black holes and other high-energy sources. There is no evidence for cosmically abundant antimatter.

Credit: G. Steigman, JCAP, 2008

But physics hasn’t yet discovered how that occurred.

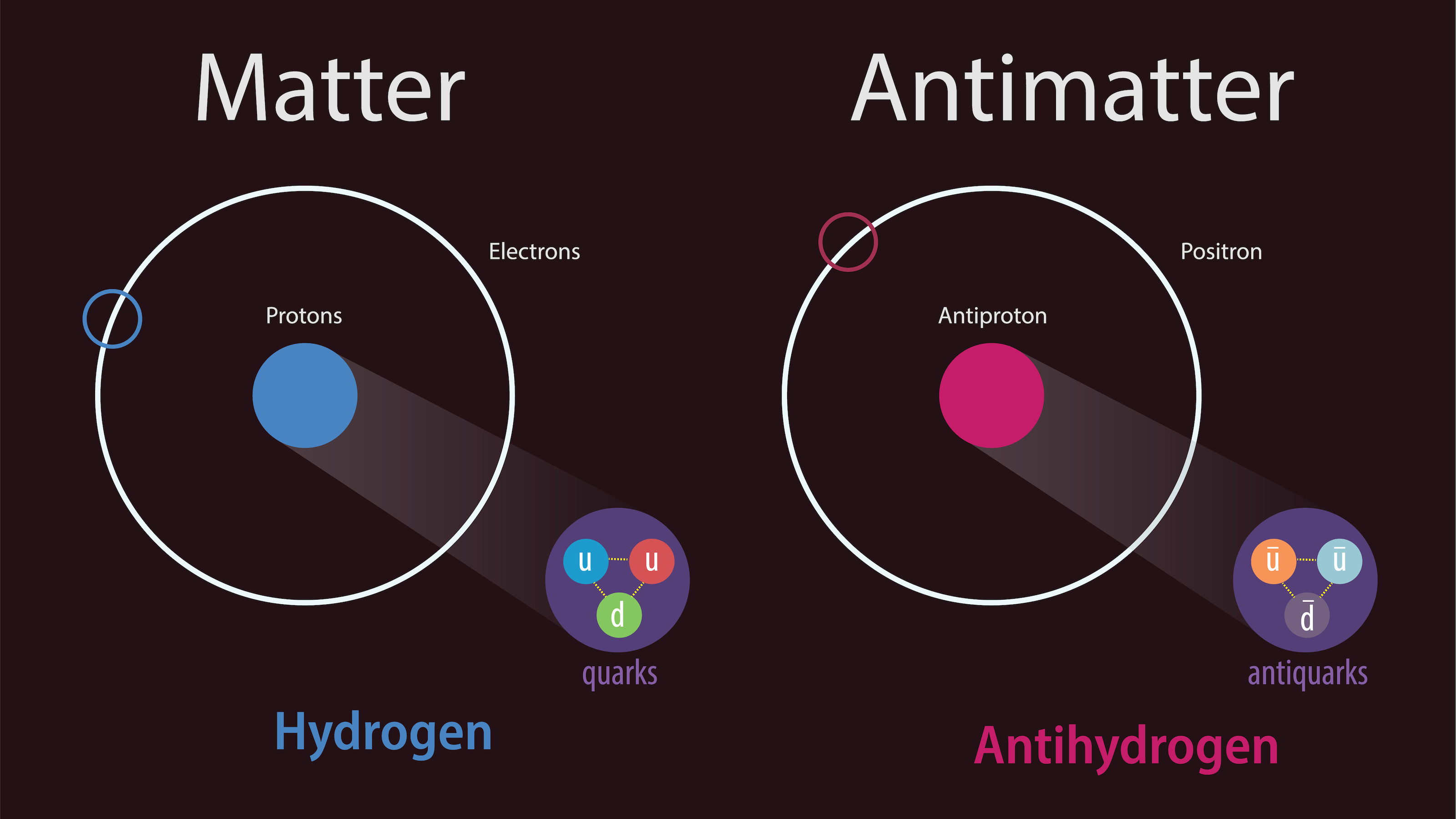

The difference between matter and antimatter is accounted for by charge conjugation symmetry: a discrete symmetry that exchanges particles for antiparticles and vice versa. Where this symmetry holds, there is an associated conserved quantity as a consequence of Noether’s theorem. Where that symmetry is violated, the conservation law no longer necessarily holds.

Credit: zombiu26 / Adobe Stock

The difference between matter and antimatter is accounted for by charge conjugation symmetry: a discrete symmetry that exchanges particles for antiparticles and vice versa. Where this symmetry holds, there is an associated conserved quantity as a consequence of Noether’s theorem. Where that symmetry is violated, the conservation law no longer necessarily holds.

Credit: zombiu26 / Adobe Stock

Einstein’s E = mc² allows us to create and destroy matter.

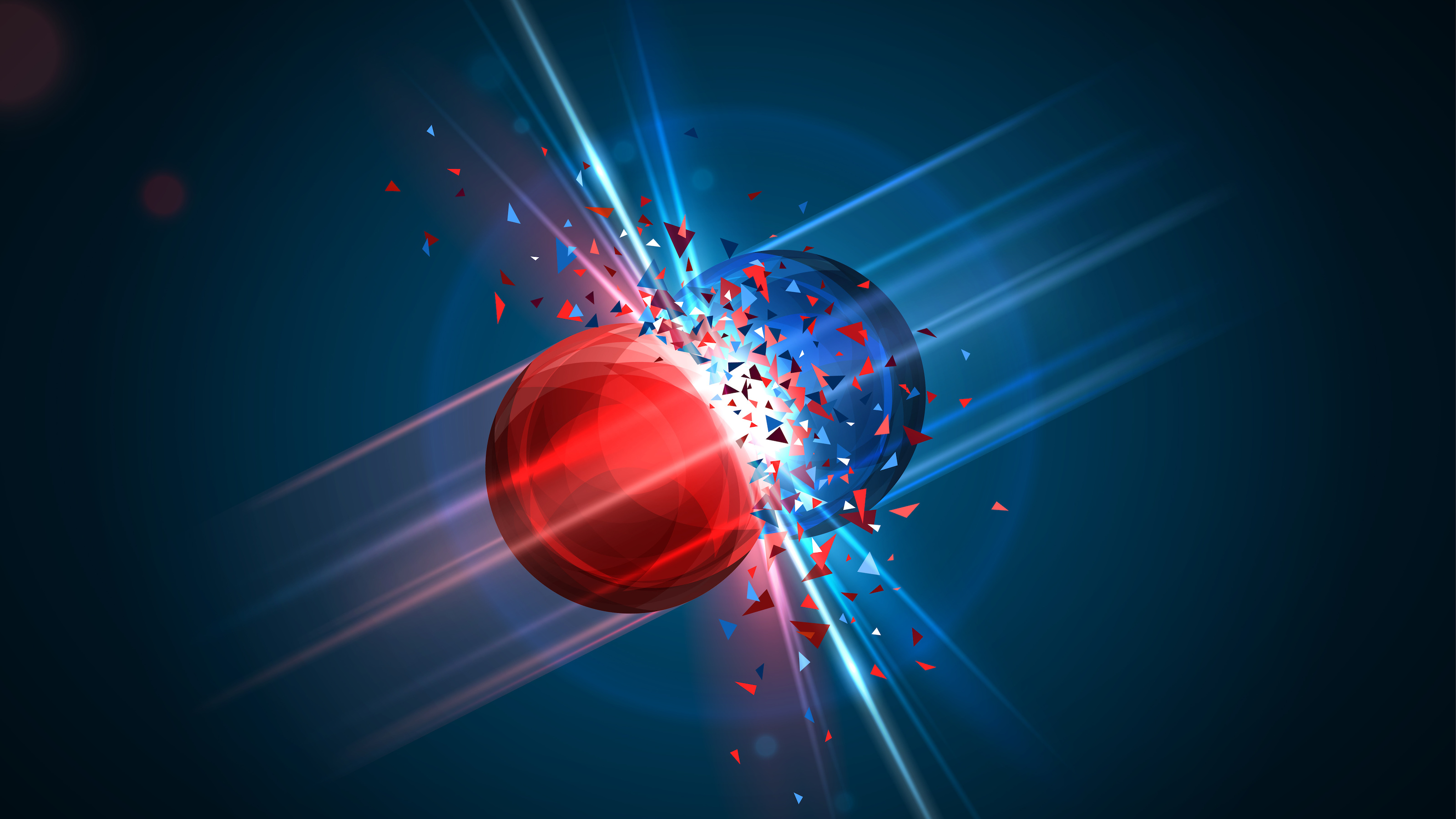

Whether elementary or composite, all known particles can annihilate with their antiparticle counterparts. In some cases, particles are matter and antiparticles are antimatter; in other cases, particles and antiparticles are neither matter nor antimatter, and sometimes particles are their own antiparticle, which is anticipated for many candidates for dark matter. The typical result of this annihilation is the production of two, equal-energy photons that fly off in opposite directions to one another, where the energy of each photon is given by Einstein’s E =mc², where m is the rest mass of the annihilating particle.

Credit: kotoffei / Adobe Stock

Whether elementary or composite, all known particles can annihilate with their antiparticle counterparts. In some cases, particles are matter and antiparticles are antimatter; in other cases, particles and antiparticles are neither matter nor antimatter, and sometimes particles are their own antiparticle, which is anticipated for many candidates for dark matter. The typical result of this annihilation is the production of two, equal-energy photons that fly off in opposite directions to one another, where the energy of each photon is given by Einstein’s E =mc², where m is the rest mass of the annihilating particle.

Credit: kotoffei / Adobe Stock

But there’s a cost: only if we create or destroy an equivalent amount of antimatter.

As the Universe expands and cools, unstable particles and antiparticles decay, while matter-antimatter pairs annihilate and photons can no longer collide at high enough energies to create new particles. Antiprotons will collide with an equivalent number of protons, annihilating them away, as will antineutrons with neutrons. After all the carnage, somehow, more matter than antimatter remains: evidence for a large initial asymmetry.

Credit: E. Siegel/Beyond the Galaxy

As the Universe expands and cools, unstable particles and antiparticles decay, while matter-antimatter pairs annihilate and photons can no longer collide at high enough energies to create new particles. Antiprotons will collide with an equivalent number of protons, annihilating them away, as will antineutrons with neutrons. After all the carnage, somehow, more matter than antimatter remains: evidence for a large initial asymmetry.

Credit: E. Siegel/Beyond the Galaxy

To create a fundamental matter-antimatter asymmetry, three conditions must be met.

Our Universe, from the hot Big Bang until the present day, underwent a huge amount of growth and evolution, and continues to do so. Our entire observable Universe was approximately the size of a modest boulder some 13.8 billion years ago, but it has expanded to be ~46 billion light-years in radius today. The complex structure that has arisen must have grown from seed imperfections of at least ~0.003% of the average density early on, and has gone through phases where atomic nuclei, neutral atoms, and stars first formed, eventually giving rise to our Solar System, planet, life, and humans.

Credit: NASA/CXC/M. Weiss

Our Universe, from the hot Big Bang until the present day, underwent a huge amount of growth and evolution, and continues to do so. Our entire observable Universe was approximately the size of a modest boulder some 13.8 billion years ago, but it has expanded to be ~46 billion light-years in radius today. The complex structure that has arisen must have grown from seed imperfections of at least ~0.003% of the average density early on, and has gone through phases where atomic nuclei, neutral atoms, and stars first formed, eventually giving rise to our Solar System, planet, life, and humans.

Credit: NASA/CXC/M. Weiss

1.) The Universe must be out of equilibrium.

This simulation shows particles in a gas of a random initial speed/energy distribution colliding with one another, thermalizing, and approaching the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. The state of reaching thermal equilibrium is when all parts of the system can exchange energy, collide with, and interact with all other parts of the system freely, and is easy to achieve for a closed, isolated, unchanging system. By contrast, the expanding Universe is wildly out of equilibrium.

Credit: Dswartz4/Wikimedia Commons

This simulation shows particles in a gas of a random initial speed/energy distribution colliding with one another, thermalizing, and approaching the Maxwell-Boltzmann distribution. The state of reaching thermal equilibrium is when all parts of the system can exchange energy, collide with, and interact with all other parts of the system freely, and is easy to achieve for a closed, isolated, unchanging system. By contrast, the expanding Universe is wildly out of equilibrium.

Credit: Dswartz4/Wikimedia Commons

2.) There must be enough C-violation and CP-violation.

Parity, or mirror-symmetry, is one of the three fundamental symmetries in the Universe, along with time-reversal and charge-conjugation symmetry. If particles spin in one direction and decay along a particular axis, then flipping them in the mirror should mean they can spin in the opposite direction and decay along the same axis. This was observed not to be the case for the weak decays, which are the only interactions known to violate charge-conjugation (C) symmetry, parity (P) symmetry, and the combination (CP) of those two symmetries as well. However, CP-violation has only ever been observed in systems containing strange, charm, or bottom quarks; never leptons.

Credit: E. Siegel/Beyond the Galaxy

Parity, or mirror-symmetry, is one of the three fundamental symmetries in the Universe, along with time-reversal and charge-conjugation symmetry. If particles spin in one direction and decay along a particular axis, then flipping them in the mirror should mean they can spin in the opposite direction and decay along the same axis. This was observed not to be the case for the weak decays, which are the only interactions known to violate charge-conjugation (C) symmetry, parity (P) symmetry, and the combination (CP) of those two symmetries as well. However, CP-violation has only ever been observed in systems containing strange, charm, or bottom quarks; never leptons.

Credit: E. Siegel/Beyond the Galaxy

3.) There must be baryon number-violating processes.

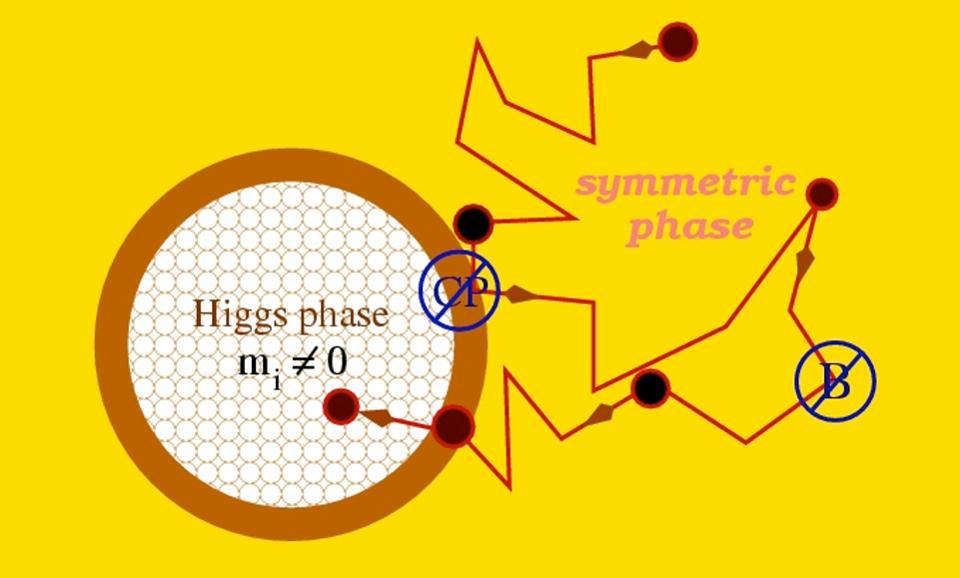

When the electroweak symmetry (the symmetry that corresponds to the Higgs field) breaks, the combination of CP-violation and baryon number violation can create a matter/antimatter asymmetry where there was none before, owing to the effect of sphaleron interactions working on, for example, a neutrino excess. This can only occur, however, if the electroweak phase transition is first-order, rather than the second-order transition predicted by the Standard Model alone.

Credit: University of Heidelberg

When the electroweak symmetry (the symmetry that corresponds to the Higgs field) breaks, the combination of CP-violation and baryon number violation can create a matter/antimatter asymmetry where there was none before, owing to the effect of sphaleron interactions working on, for example, a neutrino excess. This can only occur, however, if the electroweak phase transition is first-order, rather than the second-order transition predicted by the Standard Model alone.

Credit: University of Heidelberg

The known Standard Model exhibits C-violation and CP-violation, but not enough of it.

This illustration shows the mixing matrices for neutrinos (left) and quarks (right), which is only possible if the neutrinos and quarks have non-zero rest masses. The fact that there are non-diagonal elements in the neutrino mixing matrix indicates that electron, mu, and tau neutrinos don’t have fixed masses, but instead are superpositions of the three possible mass (1, 2, 3) eigenstates. Since the discovery of this mixing, physicists have worked hard to measure the various mixing parameters and angles between quarks and, separately, neutrinos.

Credit: S. Cao et al., Symmetry, 2022

This illustration shows the mixing matrices for neutrinos (left) and quarks (right), which is only possible if the neutrinos and quarks have non-zero rest masses. The fact that there are non-diagonal elements in the neutrino mixing matrix indicates that electron, mu, and tau neutrinos don’t have fixed masses, but instead are superpositions of the three possible mass (1, 2, 3) eigenstates. Since the discovery of this mixing, physicists have worked hard to measure the various mixing parameters and angles between quarks and, separately, neutrinos.

Credit: S. Cao et al., Symmetry, 2022

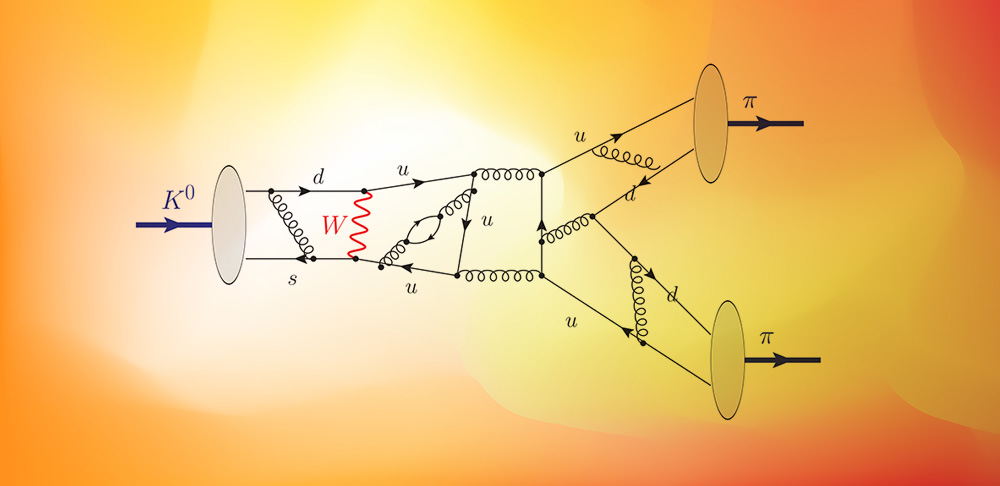

CP-violation has been observed for strange, charm, and bottom quark decays, but only in mesons.

When the neutral kaon (containing a strange quark) decays, it typically results in the net production of either two or three pions. Supercomputer simulations are required to understand whether the level of CP-violation, first observed in these decays, agrees or disagrees with the Standard Model’s predictions. With the exception of only a few particles and particle combinations, almost every set of particles in the Universe are unstable, and if they don’t annihilate away, they will decay in short order.

Credit: Brookhaven National Laboratory

When the neutral kaon (containing a strange quark) decays, it typically results in the net production of either two or three pions. Supercomputer simulations are required to understand whether the level of CP-violation, first observed in these decays, agrees or disagrees with the Standard Model’s predictions. With the exception of only a few particles and particle combinations, almost every set of particles in the Universe are unstable, and if they don’t annihilate away, they will decay in short order.

Credit: Brookhaven National Laboratory

For years, theorists have predicted CP-violation in baryons, but never saw it until now.

The LHCb detector, at 5600 metric tonnes, is 21 meters long, 10 meters high, and 13 meters wide, optimized for detecting and studying particles (and their subsequent decays) that contain b-quarks inside them. At present, there are over 1500 scientists, engineers, and technicians that work on the LHCb collaboration. Although the ATLAS and CMS detectors are more famous for discovering the Higgs boson, the LHCb detector is the only one capable of measuring CP-violation in b-quark containing baryons.

The LHCb detector, at 5600 metric tonnes, is 21 meters long, 10 meters high, and 13 meters wide, optimized for detecting and studying particles (and their subsequent decays) that contain b-quarks inside them. At present, there are over 1500 scientists, engineers, and technicians that work on the LHCb collaboration. Although the ATLAS and CMS detectors are more famous for discovering the Higgs boson, the LHCb detector is the only one capable of measuring CP-violation in b-quark containing baryons.Credit: CERN/LHCb collaboration

In 2025, for the first time, the LHCb collaboration demonstrated baryonic CP-violation.

This 2016 reconstruction of an LHCb event shows a b-quark containing baryon that decayed, producing an s-quark containing baryon along with other mesons. With observations of sufficient numbers of these decays, the LHCb collaboration, in 2025, was able to show evidence for baryonic CP violation for the first time.

Credit: CERN/LHCb collaboration

This 2016 reconstruction of an LHCb event shows a b-quark containing baryon that decayed, producing an s-quark containing baryon along with other mesons. With observations of sufficient numbers of these decays, the LHCb collaboration, in 2025, was able to show evidence for baryonic CP violation for the first time.

Credit: CERN/LHCb collaboration

Two species of b-quark containing baryons decayed to s-quark containing ones, showing robust CP-asymmetries.

The decay of neutral, b-quark containing Lambda baryons to s-quark containing Lambda baryons (plus two charged mesons), with CP-violation appearing in the case of those two mesons being positively and negatively charged kaons. The asymmetric decay amplitudes in N* resonance-dominated regions is where the CP-violation appears, with all other decays showing no evidence for CP-violation at all.

Credit: R. Aaij et al., Physical Review Letters, 2025

The decay of neutral, b-quark containing Lambda baryons to s-quark containing Lambda baryons (plus two charged mesons), with CP-violation appearing in the case of those two mesons being positively and negatively charged kaons. The asymmetric decay amplitudes in N* resonance-dominated regions is where the CP-violation appears, with all other decays showing no evidence for CP-violation at all.

Credit: R. Aaij et al., Physical Review Letters, 2025

This is consistent with their observed CP-violation in the meson sector.

Originally, the only hadrons known to exist were either combinations of three quarks (baryons), three antiquarks (antibaryons), and quark-antiquark pairs (mesons). Now, more exotic states such as tetraquarks, including the Z_c(3900) shown here, are known to exist as well. Glueballs, pentaquarks, and other exotics remain tantalizing and expected possibilities as well. Although mesons had been known to exhibit CP-violation for over 60 years, starting in 1964, the first baryonic CP-violation was only announced in 2025.

Originally, the only hadrons known to exist were either combinations of three quarks (baryons), three antiquarks (antibaryons), and quark-antiquark pairs (mesons). Now, more exotic states such as tetraquarks, including the Z_c(3900) shown here, are known to exist as well. Glueballs, pentaquarks, and other exotics remain tantalizing and expected possibilities as well. Although mesons had been known to exhibit CP-violation for over 60 years, starting in 1964, the first baryonic CP-violation was only announced in 2025.Credit: APS/Alan Stonebraker

Showing that baryons, not merely mesons, exhibit CP-violation progresses the baryogenesis puzzle tremendously.

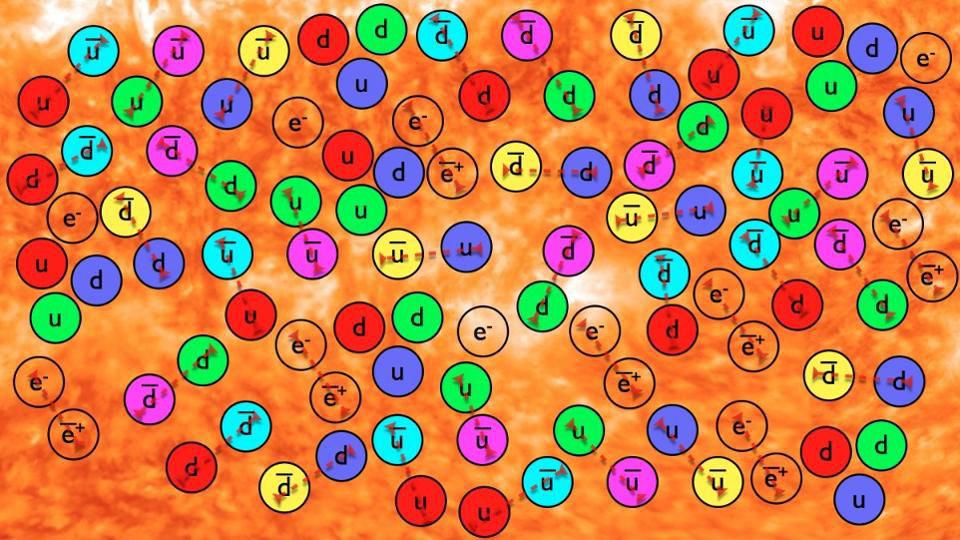

In the very early Universe, there were tremendous numbers of quarks, leptons, antiquarks, and antileptons of all species. After only a tiny fraction-of-a-second has elapsed since the hot Big Bang, most of these matter-antimatter pairs annihilate away, leaving a very tiny excess of matter over antimatter. How that excess came about is a puzzle known as baryogenesis, and it is one of the greatest unsolved problems in modern physics.

Credit: E. Siegel/Beyond the Galaxy

In the very early Universe, there were tremendous numbers of quarks, leptons, antiquarks, and antileptons of all species. After only a tiny fraction-of-a-second has elapsed since the hot Big Bang, most of these matter-antimatter pairs annihilate away, leaving a very tiny excess of matter over antimatter. How that excess came about is a puzzle known as baryogenesis, and it is one of the greatest unsolved problems in modern physics.

Credit: E. Siegel/Beyond the Galaxy

Mostly Mute Monday tells a scientific story in images, visuals, and no more than 200 words.

Tags particle physicsSpace & Astrophysics In this article particle physicsSpace & Astrophysics Sign up for the Starts With a Bang newsletter Travel the universe with Dr. Ethan Siegel as he answers the biggest questions of all. Subscribe